Renee Palma - The Reviews Hub *****

Border Crossings adapts an indigenous opera titled San Francisco Xavier and intersperses it with depictions of three events hundreds of years apart, connected by colonial violence against indigenous Latin American people. This makes THE MOUTH OF THE GODS an inventive project that turns the stuffy inaccessibility of classically renditioned opera on its head.

Only in some depictions does the play feature conversation in English, as the operatic components are sung in the nearly extinct Indigenous Chiquitano language. This creates an interesting dynamic for outsider audience members, where the narrative components most legible to them are the imperialist ones. There’s this twisted relief that comes from finally being able to understand what people are saying once the depiction of the Valladolid Debate of 1550 begins, only to find that what is being discussed is the matter of whether Indigenous people have souls and whether they are owed human decency in the Spanish evangelising mission.

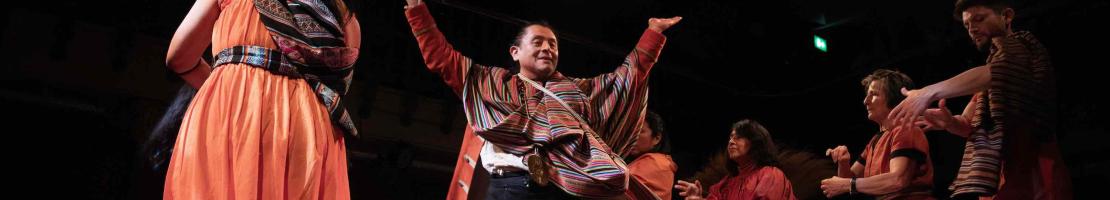

The indigenous dancers and singers, who moments ago were joined together in festivities, are left silent, only able to look but not participate in these dehumanising and nonsensical deliberations over the terms of their unjust occupation. The actors who portray the imperialism that takes on many iterations, Spanish evangelists, empire stewards in Cuzco, and capitalists profiting from environmental degradation, do well to contribute to this sinister feeling.

The only way for an outsider audience to interact with indigenous sentiments is through interpreting their art, much of which is represented in this production. Indeed, this project serves as a catalyst for much rediscovery of art for those who have ties to indigenous Latin America. It features puppets and cloth tapestries made through traditional practices and features dance and clothing drawing from that time.

In a publication freely distributed at the show, singer Rafael Montero speaks about how he has “worked to recreate a more authentic Indigenous way of singing, based on an understanding and close experience of the local way of singing this music written for my ancestors, and which I heard sung from childhood, both in churches and family gatherings.” The vocals from him and Edith Ramos Guerra modulate so clearly in moments of grief, anger, and celebration through all the characters they play.

It is a poignant reminder of all that has disappeared from the records, eroded by time, and forcefully removed by those in power. The records most accessible to those interested in the rich histories of indigenous Latin America are the ones kept by the Europeans, which are paternalistic, violent, and sickeningly egoistic. Further, by recreating the assassination of the leader of the Indigenous Lenca people and Honduran climate activist Berta Cáceres, Border Crossings shows the audience the lengths through which those in power go to hide their centrality to the violence even as they make a spectacle of it.

The production makes full use of Hoxton Hall. Talented musicians narrate the mood through their playing on the stage. There’s creative use of the dimension of the space, with imperial forces standing upon higher platforms as their brutality comes down upon otherwise joyful people. Poetry and translation are projected above the production, shaping the grief the audience feels over the events taking place.

This production is simultaneously a meditation on colonial violence and a community-building project for those largely estranged from their history, and the dual functions of it bleed into every component.

Hoxton Hall comes alive with the sights and sounds of South America in Border Crossings' THE MOUTH OF THE GODS - Erin Caswell - Salterton Arts Review ****

I was thinking to myself on the way home from THE MOUTH OF THE GODS: why does it feel so different? Most productions have a long development time during which various creative processes, research and experimentation occur. Why does this one feel special? I came up with a couple of reasons for this.

Firstly, the richness of the co-creation. THE MOUTH OF THE GODS isn’t a straightforward theatrical or musical work. It combines rediscovered music enriched with Western and non-Western instruments, dance, theatre, textile work and embroidery, storytelling, and puppetry. Each of these elements required profound research. Singer Rafael Montero went to the Misión de San Javier in Bolivia where the indigenous Chiquitano opera San Francisco Xavier was composed around 1720. Master embroiderer Bella Lane and choreographer Jessica Mirella Luong drew inspiration from the collections of the British Museum. Putting the unknown indigenous composer’s music back together was a collaboration between a musicologist, musicians, the Horniman Museum and its musical instruments collection, and elders familiar with the almost extinct Chiquitano language and the associated cultural context.

The second reason is the local and global nature of the work. Indigenous South American traditions and the Spanish colonial context transported to London, with local people contributing stitch by stitch or step by step to the final result. What’s an absolute delight to see something like this on my doorstep!

The Traditional and the Contemporary

I’ve already described a lot of what THE MOUTH OF THE GODS is, but let me do it properly. It is, according to theatre company Border Crossings, an immersive production taking audiences “on a powerful journey from the oppressive colonial era towards renewal and hope”. Baroque music underpins it. A system of “reductions” enabled (or sometimes forced) Indigenous South American people to live in missionary settlements in exchange for adopting Christianity. This gave many an opportunity to learn Western traditions of music and composition from Jesuit priests. The Indigenous composers didn’t often sign their work, but some of the work survives nonetheless. It’s often an example of syncretism, the synthesising of different religions (in this case indigenous and Christian) which in the South American context made a foreign religion more comprehensible as cultures collided.

THE MOUTH OF THE GODS similarly brings traditional South American cultures and beliefs together with what was imposed on it by European colonisation, with Baroque compositions at its core. We start with a blessing, before a scene symbolising the end of pre-colonisation ways of life, using movement and puppetry. A surprising theatrical scene recreates the 1550-51 Valladolid Debate, a moral and theological debate over the conquest of the Americas. A later scene draws parallels with the continued lack of respect for indigenous views and autonomy, as seen in the assassination of activists like Berta Cáceres.

The complexity of cultural exchange is a thread running through THE MOUTH OF THE GODS. The compositions of the reductions were simple: just a melody line upon which musicians would elaborate. So although it is music in a Western tradition, it is also music that would have had an indigenous element from the outset. In this production this fusion is embodied by ensemble El Parnaso Hyspano who blend traditional Western and South American instruments. Techniques old, new and cross-cultural similarly combine in the movement and textiles. It’s a story of perseverance and adaptation: what is still here rather than what has been lost.

Staging History, Culture, Art and Activism

It is not an easy thing to do, to fit this much into a 90 minute performance. And frankly not an easy thing to try to communicate to audiences. I thought on the whole, though, that THE MOUTH OF THE GODS was successful. There were a few elements I would change: I found it inconsistently surtitled, for instance, and couldn’t quite follow the narrative of all the dance sequences. And I think a synopsis of the scenes and music in the excellent programme would have been a great addition. But it blends many different art forms nicely. There’s even some light relief in the form of the executioner (Tim Hudson) of Túpac Amaru II and his wife Micaela Bastidas (played by Montero and Edith Ramos Guerra), who is more concerned about his working conditions than the morality of the task before him.

It is also a treat to have Peruvian soprano Edith Ramos Guerra as part of the cast. I especially loved hearing her sing in both operatic and traditional styles, showcasing a range of vocal talents. She is regal, and creates an immediate emotional connection with the audience.

A final note on the venue. Hoxton Hall is a wonderfully-intact Victorian music hall. Audiences can sit in the galleries, or can stand around the raised stage. The latter is a more immersive experience, while the former gives a great bird’s-eye view of the textile art. Those in the galleries may struggle to read the surtitles when present, however.

All in all, THE MOUTH OF THE GODS is one of the most unique and special experiences I’ve had this year, and that comes from someone who sees a lot of performances. Do see it if you can, you will never have this opportunity again. And best of all, it is free!

Eleanor Thorn - South London Community Matters

When Border Crossings and its artistic director, Michael Walling, set out to create THE MOUTH OF THE GODS, a show with strong references to the colonial history, destruction, theft and disrespect of native Latin American people and lands from the time the colonisers arrived until now, they would not have realised the pertinence to what is going on now in the Middle East. But one big take away, as I reflect on the show, is how history, despite the will of so many, does repeat itself, and atrocities that went on in the past, well, many are being wreaked right now in Gaza, and weirdly, under similar pretences: the righteous against the heathens. For God willed it that way.

When Border Crossings and its artistic director, Michael Walling, set out to create THE MOUTH OF THE GODS, a show with strong references to the colonial history, destruction, theft and disrespect of native Latin American people and lands from the time the colonisers arrived until now, they would not have realised the pertinence to what is going on now in the Middle East. But one big take away, as I reflect on the show, is how history, despite the will of so many, does repeat itself, and atrocities that went on in the past, well, many are being wreaked right now in Gaza, and weirdly, under similar pretences: the righteous against the heathens. For God willed it that way.

THE MOUTH OF THE GODS is not only about those great injustices, but is also an incredibly intense celebration of pre-Columbian art and traditions that weaves together the early music of the Spaniards, their dances and their interactions with local traditions, glorious artwork, puppetry and embroidery that is the culmination of many months of research and handiwork by people in our London communities, mostly women with Latin American connections.

What took me out to the opening night was the involvement of Jose Navarro, an extraordinarily creative and gifted Peruvian puppeteer. Wherever he is bringing to life a new creature, this one a large straw-haired Chancay doll handled by himself and three other puppeteers, magic is guaranteed, and this show does not disappoint. What wowed me from the moment I took my seat up in the highest gallery, was the magnificent floor of the raised stage that occupied all of what would usually be the stalls. Three panels, masterminded by Bella Land, that later in the production glow in parts, thanks to its use of fluorescent paint, feature a fish, a hummingbird, a condor and geometric, crying human figures. In all of this Victorian venue’s nearly ten years since its restoration, I am sure no other show will have brought the space alive quite so imaginatively. Positioned on the main stage where you would usually expect to find the performers, was El Parnaso Hyspano Ensemble featuring harpsichord, played and led by Matthew Morley, with percussion by Johnny Figueroa Rodriguez. Provoking instant recollection of famed religious portraits by Velazquez and Francis Bacon, a central door behind the ensemble opens and a cardinal oversees the 1550 debate between Sepulveda and Las Casas as to how the evangelising should be carried out. Later, we are in 1781 and witnessing the drawing and quartering of Inca rebel Tupac Amaru II.

As well as creating community projects that have involved researching archives at the British and Horniman Museums over months, looking at objects and material that date back as far 3000BC and working with local schools, the strength of this show stems from its music and its two professional singers, Peru-based Edith Ramos Guerra and UK/Germany-based Rafael Montero. In the last 30-40 years, across Latin America, ancient manuscripts have come to light and in the second half of the show we are treated to the early Indigenous opera, San Francisco Xavier. The delicacy and linguistic richness of instruments, drums, voices, married with the European and Indigenous dance steps makes this a profound experience. Finally we are brought back to reality by two current day businessmen discussing how they can continue to exploit and create wealth, before homage is paid to Honduran environmentalist Berta Caceres and others who have striven to preserve the Planet at great cost to themselves, and who must not be forgotten.

The show is not, as Walling explains, about victimhood. It seeks to go beyond being an exercise in reparative justice. Resistance, a word we are hearing daily in relation to the people of troubled parts of the world, is key: resistance to colonisers, to the preservation of memory and history, and to encroaching threats to Nature. As Edith Ramos Guerra puts it, “it is the expression of many voices that are often forgotten or silenced, ignored or unwritten, even in the histories of their own people”. With resistance, there is hope.

Quoting Michael Walling in the programme, “The revitalising of Indigenous culture is not only of huge significance for Indigenous people themselves, but for all humanity” I am reminded of Nelson Mandela’s phrase so often heard of late: “For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

Hoxton Hall, like Wilton’s Music Hall, where I recently saw The Pirates of Penzance, is a special one, and accompanying me was a friend who had spent a good deal of time recording and gigging in the neighbourhood, but he had never been before. This is a great opportunity to discover one of London’s hidden gems, standing next to the stage or seated in the galleries. THE MOUTH OF THE GODS is supported by the Heritage Fund and entry is free of charge to all.

Tim Hochstrasser - Plays to See *****

Border Crossings are well known for their innovative cross-cultural productions, and in this venture they have truly excelled themselves. The Mouth of the Gods is a lavish, hybrid work that encompasses opera, dramatic reconstruction, dance, puppetry, community singing and symbolic textile embrodery, all within a musical framework of Baroque and indigenous Latin American instruments. It is a supremely inventive cultural collage that celebrates the fusion of indigenous and Spanish colonial cultures while commemorating the often tragic history of repression and exploitation that resulted. It achieves this in a way that should make its mark on people of all ages.

Border Crossings are well known for their innovative cross-cultural productions, and in this venture they have truly excelled themselves. The Mouth of the Gods is a lavish, hybrid work that encompasses opera, dramatic reconstruction, dance, puppetry, community singing and symbolic textile embrodery, all within a musical framework of Baroque and indigenous Latin American instruments. It is a supremely inventive cultural collage that celebrates the fusion of indigenous and Spanish colonial cultures while commemorating the often tragic history of repression and exploitation that resulted. It achieves this in a way that should make its mark on people of all ages.

The collage comprises two different categories of material – in the first half the performers reconstructed items from musical collections preserved in Jesuit communities in northern Peru, some vocal and some instrumental, but all the work of indigenous composers imitating European Baroque style. In the second we receiveed a performance of a whole opera written in Chiquitano, essentially a dialogue between St Ignatius Loyala and St Francis Xavier. Breaking up the musical elements were three dramatic episodes delivered by actors in English devoted to crucial events in Latin American history – the Valladollid debate of 1551 over the ethics of Spanish colonialism, the cruel execution of resistance hero Tupac Amaru in 1781, and the murder of indigenous environmental activist Berta Caceres in 2015.

As you might imagine from this summary, there was a huge number of themes and aesthetic strands in play at any one time, testament to the ambition of director Michael Walling. Not everything worked perfectly on press night, especially the surtitles, but never mind. If, as Wagner suggested, opera should aspire to be ‘the total work of art’, then this production hit that target as far as is humanly possible. There was hardly any aspect of Latin American culture and history that was not referenced or alluded to in some way. Moreover, the excellently detailed programme revealed how much research had gone into the show, with the embroiderers and puppeteers seeking inspiration from the British Museum and the instrumentalists investigating the resources of the Horniman Museum.

At the heart of the sequence were two singer-performers well versed in this repertory. Edith Ramos Guerra and Rafael Montero are equally adept in Baroque and folk styles, with Ramos Guerra in particular presenting great technical skill and tonal purity. Both of them were entirely abreast of a huge amount of text in various languages. The instrumental ensemble of El Parnaso Hyspano offered a fine blend of colours, with mournful cello and indigenous percussion very much to the fore. The puppeteers were prominent, indeed dominant, in two episodes where a human figure and a condor played symbolic roles, and professional dancers mingled with community performers to memorable effect in moods of merriment and lamentation. A chorus of local children interacted memorably with Ramos Guerra and Montero.

Three actors took on a variety of mainly unsympathetic roles, but to compelling effect. Danny Scheinman inhabited Sepulveda and a slick modern international businessman with chilling authenticity; Simon Rhodes found more humanity and conscience in the figure of Las Casas; and Tim Hudson developed a series of bluffly brutal characterisations as a Cardinal Inquisitor, a professional executioner, and a contemporary entrepreneur of assassination.

The collaboration between the design team was exceptional. A raised platform with two staircases leading up to it was covered with a symbolically detailed textile covering, and on this the main action took place. Specially woven mantles and costumes of rare device were ritually introduced at various points, and Hoxton Hall itself played a notable role, with its intimate combination of shabby chic decor and elaborate wrought iron balconies. Wiltons will have to look to its laurels!

There was a lot more in this evening than could register at first hearing, and it is very much to be hoped that further performances can be developed, not least in the Latin and Southern American countries whose heritage is here so richly evoked.